By Eshwer Kale and Karan Misquitta

The Maharashtra Groundwater (Development and Management) Act 2009 presents an answer to some of the state’s water scarcity woes and is an important step towards sustainable groundwater management in the State. However, the institutional structure put forth by the Act is unwieldy and poorly outlined. There is a need for innovative institutional designs that would enable operationalization of this act. Given the informational and knowledge requirements for understanding groundwater, coupled with the challenges of mobilizing support for its sustainable management , there is a need to create a cadre of “jalsevaks”. These jalsevaks will work with communities to demystify groundwater, and navigate the complex socio-political terrain in order to arrive at more equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Since the last decade, Maharashtra is facing severe water scarcity, for irrigation as well as domestic needs. The difficulties and troubles faced in accessing basic water (water for drinking, domestic and sanitation needs) is becoming a bigger challenge with each passing day. In a few scarcity pockets of the state, water is being supplied through trains and tensions have come to boil so much so that water tankers require police protection. These incidences substantiate how precious water has become in background of consecutive drought. Although water scarcity is largely perceived as a result of natural phenomena occurring because of less and uneven rainfall, this condition is aggravated due to over-extraction of groundwater for irrigation.

The recent Maharashtra Groundwater (Development and Management) Act 2009, which came into force in June 2014, accepts the principle of subsidiarity which proposes to give the function and authority of groundwater management at lowest level by formation of Watershed Water Resource Committee (WWRC) to be constituted among a cluster of at least 11 villages. On the other hand the Center’s Model Bill on ‘Conservation, Protection and Regulation of Groundwater 2011’ proposes the formation of Gram Panchayat Groundwater Committee (GPGC) at the Panchayat (village) level. The challenge in operationalizing the WWRCs is that mobilizing and organizing at the cluster level is difficult. Hence, we must take cognizance of institutional structure suggested in the Model Bill and strengthen village level institutions with the WWRC functioning as a federating body.

In both these policy documents the role of organizations such as Groundwater Survey and Development Agency (GSDA) officials is crucial in providing technical support to village communities for preparing and implementing groundwater security plans and prospective crop plans. Overall, the role of external facilitators or experts in motivating, supporting and facilitating farmer communities to adopt appropriate groundwater practices is well acknowledged in overall groundwater management efforts. However, there is little clarity on the shape that the required institutional mechanisms will take.

Considering these facts, few GOs, NGOs, and Civil Society Groups since last few years are making efforts to promote community based groundwater management initiatives by regulating groundwater extraction and promotion of water-use efficient practices amongst farmers. To achieve this, many institutional mechanisms and models have been tested which have resulted in some success.

Early attempts tended to be restricted to particular villages like Ralegaon Siddhi and Hivre Bazar. In recent decades, much of the work undertaken on groundwater governance in the country has focused on the sustainable use of groundwater as a common pool resource. While these programmes (the Andhra Pradesh Farmer Managed Groundwater System being the most prominent and large scale) have achieved some success in improving groundwater resource status through crop water budgeting, serious concerns have emerged over their sustainability as well as distributive impacts. These projects focus heavily on developing an effective institutional infrastructure and creating and disseminating local level knowledge and information on groundwater in order to improve groundwater governance. However, there are significant transaction costs associated with these activities and a key constraint that emerges is the inability to sustain rainfall & hydrological monitoring activities as the projects come to a close.

In this context, working with communities to address the disastrous water scarcity situation, WOTR recently launched an applied research project supported by the Hindustan Unilever Foundation. A central idea of the project is to create a local cadre of jalsevaks in the village communities who are expected to enable and facilitate the adoption of better water management practices. Jalsevaks are the youths trained by WOTR, who work towards facilitating behavioral change among groundwater-dependent farmers, both at the individual and collective level. It is also important to note that these jalsevaks are intended to act as a semi-professional cadre that supports participatory groundwater management.

While collective action and community ownership still form the bedrock of effective water stewardship, it is necessary to acknowledge the need for dedicated actors to play an enabling role among the community. For this purpose, it is imperative to move past the often convenient logic of voluntarism. Often the emphasis on voluntarism fails to recognize that sustainable resource management requires sustained efforts, nested within an appropriate organizational and institutional structure. Given the presence of legislative support for groundwater management in the form of the 2009 Act, it is imperative that in the near future (after the effectiveness of the jalsevaks has been established) they are incorporated into its institutional structure.

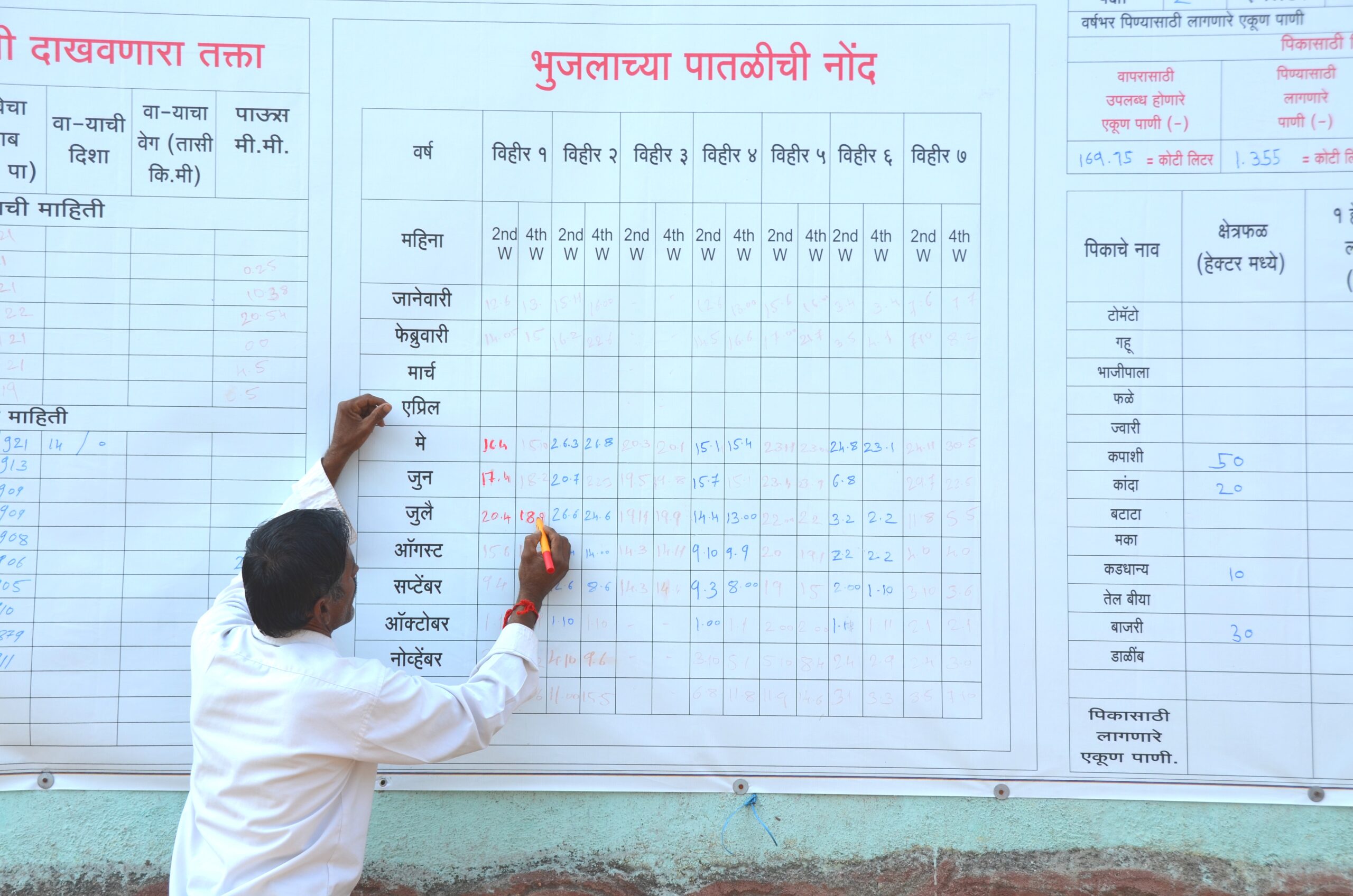

The jalsevaks facilitate and support the preparation of village and cluster level Water Stewardship Plans, comprising water budgeting exercise, prescribing appropriate crop plans, water-use efficiency measure, and different water augmentation activities. Jalsevaks also make efforts to guide farmers and villagers to get support from different government schemes that are aligned with these activities and goals. As of now 38 jalsevaks in the project villages across five districts are working on collecting necessary baseline information on water resources and water-use at the village level for further designing of water stewardship plans.

The demystification of hydrogeological knowledge coupled with the spirit of social entrepreneurship promoted among local youth will strengthen local knowledge on water resources and its efficient use. This has the potential to change the groundwater extraction game in existing groundwater resource use pattern. The blind race of groundwater over-extraction amongst farmers and the resultant scarcity has mainly occurred because of lack of appropriate hydrogeological knowledge, and the absence of an institutional setup that incentivizes collective action and the adoption of water-use efficiency practices. The jalsevaks may emerge as the CHANGE MAKERS in groundwater exploited pockets to make village communities water literate and more sensitive to water-use practices.