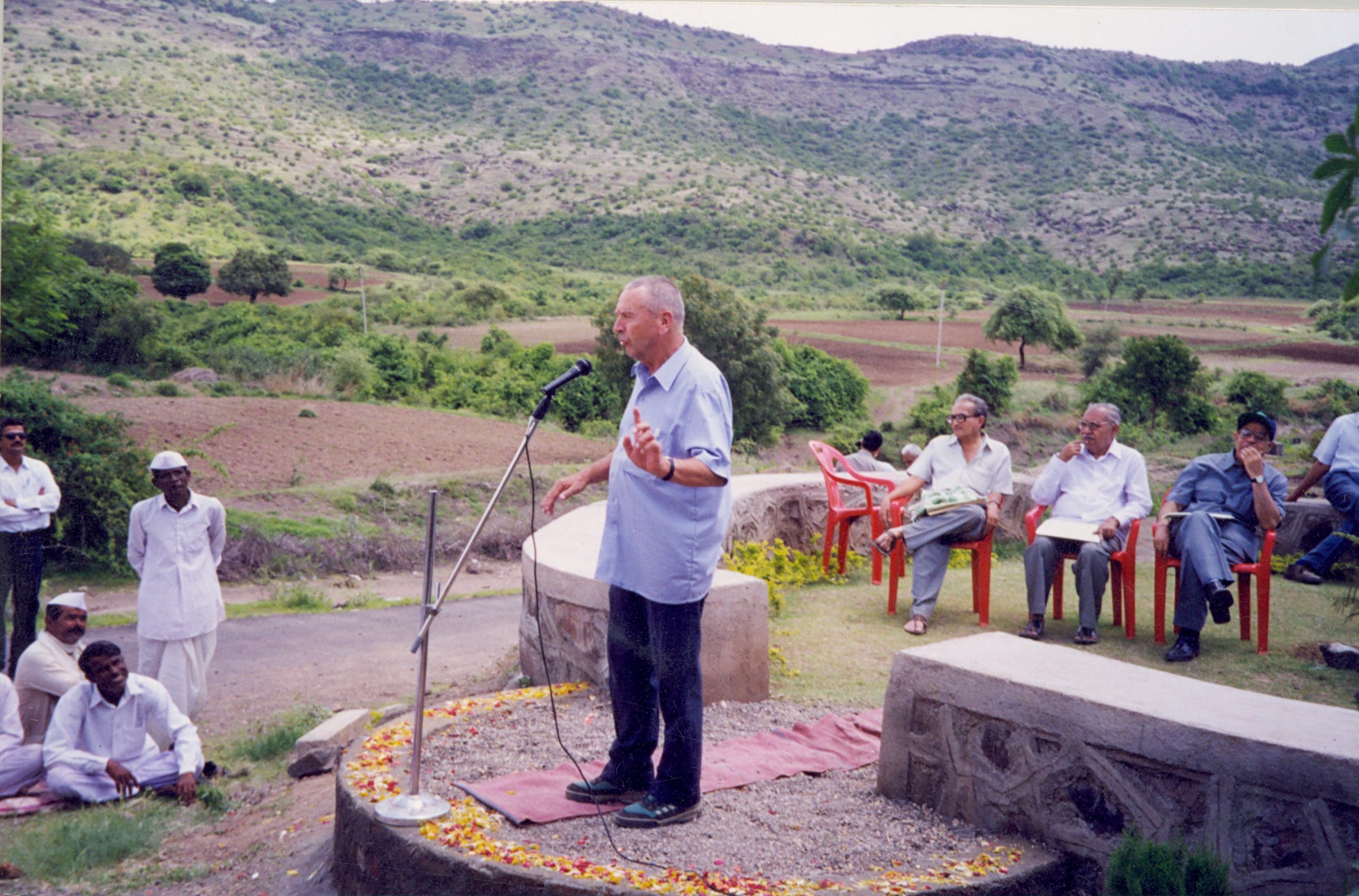

Hermann Bacher, popularly known as Bacher Baba or Father Bacher, initiated the people-led watershed movement in rural India, working tirelessly for the upliftment of the poor and marginalised communities.

Born on the 12th of October 1924, in mountainous Muenster, an alpine village in Switzerland, Father Bacher came to India in 1948 at the young age of 24. For the next 60 years, he selflessly worked in rural India, particularly Maharashtra, working towards poverty alleviation and rural development. His goal in life was to support the sustainable growth and well-being of the vulnerable and disadvantaged communities in rural India.

When Maharashtra was hit by a severe drought in 1972, Father Bacher realised that watershed development was the only sustainable way out of drought, and poverty. He would often pithily put it in Marathi, “पाणलोटाशिवाय दुष्काळाला पर्याय नाही!” (Without watershed development, there is no solution to drought.)

Father Bacher’s work impacted millions of lives but what stood out was his humility and simplicity, his depth of knowledge, his love and commitment to uplift the poor and his unique ability to inspire people to action by his own example of sacrifice and purposeful action. On the occasion of his 98th Birth Anniversary, we share a few anecdotes from two of the lives he touched.

Those Countless Cherished Moments

-Vitthal Shewale (Editor of Ujjval Udyasaathi, Retired Professor, and Founder of Nisargayan)

Although I have never met Rishi Agasti, Sane Guruji, or Gadge Baba, Bacher Baba’s personality embodied the likeness of all three. It is a matter of pride for us that I had the chance to not just see and meet him, but also experience his companionship and love.

In the 90s, I was a Marathi Professor at Sahyadri College of Sangamner. Bacher Baba’s work was already well recognised and I invited Baba to visit our institution for a guest lecture. That was the first time I met him. On hearing that about my NGO (Nisargayan) and the work we did, he promptly asked me, “Why don’t you adopt a village for a watershed?”

“My organisation is very small, Baba! It wouldn’t be possible for us to do it,” I responded right away.

He replied, “It is not a question of whether the organisation is small or big; what matters is how much grit and passion you have to make something possible. To make anything successful, two things must be kept in mind: one is rigorous planning, and the other is effective implementation.”

So inspired was I by his words that my organisation went ahead and successfully undertook a major work in watershed development at Sarole Pathar in the Sangamner tehsil of Ahmednagar district. From this point onwards, our friendship developed further.

He would frequently tell villagers and others that if World War III ever happened, it would be fought over water. He worked for water management and agricultural development throughout his life. Baba had an undying love for soil and water.

Baba was also very clear on the function of research – Any research not beneficial to farmers is useless was his position. I recall a humorous anecdote related to this: Once Baba asked a villager to draw a circle on a blank piece of paper. He then asked him to write bhakri on it and then eat the bhakri. The villager was perplexed, to which Bacher Baba said, “No matter how good the bhakri looks on paper, it cannot be eaten. And so it is with research. No matter how deep and laborious it is, it is pointless if it cannot be used for farmers.”

Baba’s disdain for the conceited was very well known. When a certain individual kept patting his own back “I’m deaf. I can’t hear,” muttered Baba, interrupting the other man.

Baba was as tall as the sky. Even if he isn’t here with us right now, his thoughts are with us; we cherished his company; his motivation and pursuit still serve as a model for all of us. Baba lives with us through these countless cherished moments.

A Yogi Devoted to Action

-Dr. Y S P Thorat ( Former Chairman-NABARD, and former Executive Director RBI)

On the 14th of September, 2021, my wife called me from Chennai to inform me that Father Bacher was no more. For a moment, time stood still, and my mind went back to the flight I had boarded to Geneva many years ago, sitting next to an elderly person who was going through a bunch of papers. He was on a window seat, and I was next to him reading a book. He glanced at me briefly but did not say anything. At lunch, we both put down the reading and simultaneously looked at each other.

“I am Bacher,” he said.

“Thorat,” I replied.

He told me he was on his way home and asked me what I was going to Zurich for.

“To lecture at a university,” I replied.

“Indeed,” he said, “on what?”

“The state of Indian agriculture,” I said; his eyes lighting up.

“Are you an academician?” he asked.

“No, just a public servant. I work in the Reserve Bank.”

“Someone spoke to me about you,” he said.

“I was surprised that he or anyone should have heard of such an inconsequential person as me,” I said.

He laughed. “That’s not important. But tell me, what’s the crux of your argument?”

I told him, and we discussed it. He listened intently, asking searching questions from time to time.

“What bothers you the most?” he asked.

I remember mentioning the uneconomical size of the majority of Indian land holdings coupled with their location in dryland areas.

“And what’s your prescription?” he further inquired, pressing the point.

“I’m not sure,” I began cautiously.

“Why not?” he said, with a tinge of harshness. “You are a policy maker. You can’t be tentative about something that is a matter of life and death. Do you know what the farmer needs most—not handouts, but water? What do you know about watershed development?”

“Not very much,” I replied honestly.

“Well, that’s a fair starting point. Let me explain.” And for the rest of the flight, he took me through the theory and practice of integrated watershed development. Little did I know that the chance meeting would lead to our paths crossing numerous times at RBI and NABARD.

During the flight, he asked where I was staying in Geneva, and I intuited that I had no idea how to make my way there. After we got off the plane, he insisted on walking me to my hotel as a very kind act.

As we shook hands, he said, “You are a Maratha, aren’t you?”

Yes, I replied.

“What bread do you eat?” he asked.

“Bhakri,” I replied. “Well, there you are,” he said. “Bacher and Bhakri.” Even today, when I bake bread, his smile adds to the flavour.

When I read the news of his demise, it struck me that if the balance sheet of Father Bacher’s life was summed up in four lines, it wouldn’t have held the rest of us:

India was his Karmabhoomi. He launched the Indo-German Watershed Development Programme and made “ridge to valley” a common noun in development literature. His plan was to bring together villagers, panchayats, the government, elected officials, funders, and everyone else who had a stake in rural development and encouraged them to work together. He involved local communities in each project and placed equal emphasis on social and technical aspects at the implementation stage.

I found Fr. Bacher to be a Yogi at the deepest level, devoted to action and not to the consequences. He never marched with the herd, but alone to a tune audible only to him.

The living presence of Bacher Baba, a Jesuit priest and man of God, a selfish crusader for the poor and the voiceless, reminds all of us that God Almighty has not given up on his creation.

Father Bacher’s silent work has created a lasting impression that will dwell on our minds and hearts forever. His work transcended the boundaries of an artifice called a nation which is why even though his ‘janmabhoomi’ was Switzerland, his Karmabhoomi was India. His journey from being “Father Bacher” to “Bacher Baba” and now “Dev Manus” shall be fondly remembered by all of us at WOTR, the communities he touched, and the regions which now see an abundance of natural resources and livelihoods.