by Nikhil Nikam

As we all know, in the early stages of COVID-19 in 2020, there was no vaccine or treatment available to protect people against infection. As infections increased, the government implemented lockdowns, closed borders, and imposed travel limits to prevent the virus from spreading—all of these preventive measures to keep the epidemic under control affected the global economy. Food processing plants, industrial units, and all other non-essential enterprises in India were shut down during the initial phase of the lockdown, affecting the marketing and trade of agricultural products and inputs.

While, social media has both benefits and drawbacks, rumors travel faster and further than truth. For example, unsubstantiated ‘fake news’ and rumors were circulating on messaging platforms, claiming that the coronavirus could be transmitted via poultry birds. As a result, people stopped consuming eggs and chicken; many backyard poultry owners decided to bury young chicks and fully matured birds to save money on the future costs of keeping them alive without any monetary returns. Previously bird flu (avian influenza) hit the industry hard in 2006. But then, the fears were based upon facts. This was not the case in the current corona crisis.

Travel and movement limitations impacted goat rearing, as most pastoralists prefer grazing choices for their goats over stall feeding, following traditional practices. Only the dairy industry was unaffected by the lockdown since milk is considered an essential product.

Negative impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture and allied sectors in the First wave (2020)

Due to the nationwide lockdown, markets and food processing industries were shut down. As a result, large quantities of fruits, flowers, and vegetables were wasted due to the lack of storage/ cold storage facilities available in the village. So farm owners opened their farms and distributed free fruits, vegetables, and perishable farm produce to the villagers. Unfortunately, some local traders took advantage of this situation and bought produce from farmers at lower rates and sold it at high prices in the cities or hoarded it to sell it later when the prices go up.

When farmers were preparing for the monsoon season, the cost of agriculture input was relatively high due to increased demand; there was no supply as most industries were closed. Earlier, farmers used to procure agricultural inputs on credit which was accepted, but now shopkeepers and traders are unwilling to provide credit facilities to the farmers due to uncertainty of life because of the pandemic. All these constraints and challenges related to agricultural trade, the shortage of agricultural inputs, and the sale of produce, caused farmers to change their cropping patterns in the kharif season in 2020. They preferred to cultivate crops with long shelf life rather than perishable ones.

WOTR’S COVID-19 Rapid Response

There were many challenges, but farmers who generally face uncertainty, have their ways to deal with them. To back up that strength, WOTR supported many farmers in the project villages through humanitarian aid and various training events that helped continue agriculture without interruption.

The Farmer producer organization (FPO) is encouraged and facilitated across WOTR’s project villages. A group of neighboring villages collectively form one FPO through which they can collectively sell their produce directly to the food processing units or big traders for a fair price and procure farm inputs in a large quantity directly from the manufacturer at discounted prices. In this process, the farmers save a little and earn a little more than the individual trading options.

During the pandemic the FPOs were functioning; they helped farmers sell their produce even when the local markets were closed. Moreover, they reduced exposure of villagers to the virus. As a result, FPOs from project villages of Odisha, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, and Telangana collectively sold around 13,000 quintals of rice, wheat, fruits, and vegetables, amounting to Rs 2.5 crore rupees, which directly benefitted about 2000 farmer households from these states.

To reduce the cost of cultivation and the losses incurred in the field, the farmers implemented a crop intensification system and rice intensification during cultivation. Also, given the stagnant market conditions, farmers were not certain that they would get good market returns in the following season. So instead of farming to trade, they grew green manure crops that does bring in direct economic returns but helps in restoring soil health which then increases crop productivity in the next season.

When the markets were closed and there was a shortage of pesticides and fertilizers, farmers prepared organic pesticides and fertilizers using the organic formulation techniques guided by WOTR during the pre-COVID period.

In this picture, women are preparing Dashaparni Ark. It is an organic pesticide made using ten different types of plant leaves and other local ingredients, which is highly effective and works on most pest attacks.

Positive impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture & allied sectors in the First year (2020)

Besides the negative impacts of COVID-19, there were also some incidental benefits observed. Due to the unavailability of the retail market, there has been an increase in contract farming. The way crop insurance covers climate-induced losses, contract farming also transfers market-related risks to someone else. It thus ensures farmer’s income security.

Apart from income security, farmers have also tried to bring food and nutrition security. For example, women farmers have developed their own kitchen gardens and have implemented multilayer farming. They avoided going to the market to purchase vegetables. Besides, this farming provided additional income through the sale of the surplus produce from the kitchen gardens.

Also, when the migrants returned to the villages during the lockdown, it increased the labor force into agriculture. And migrants were not sure when the lockdown would get lifted. Therefore, to secure the livelihood source in the village, migrants used their savings to build agricultural infrastructure eg they dug wells, borewells, and did redevelopment of barren land to increase the area under cultivation. Besides, as an alternate source of livelihood, migrants also invested in small ruminants like goat, sheep, and poultry and such liquid assets, which they could sell whenever they could return to the cities.

Agriculture and the market in 2021

Farmers are now adapting to the new normal situations. While the markets are partially open, there is no agricultural inputs shortage as in 2020. However, as the manufacturing industries are in the phase of recovering the losses of last year, the prices of the agricultural inputs have been increased by 5 to 10 percent. COVID-19 restrictions still affect the retail sale of the farm produce; hence, wholesale marketing through the FPOs and contract farming are preferred. The restrictions on social events have also affected the floriculture sector. Similarly, it has affected fruits and vegetable crops with low shelf life. The fear of unexpected lockdown in forthcoming waves of COVID-19 drives the crop planning for the upcoming season; farmers prefer long shelf-life crops over perishable crops might strike the agricultural market again.

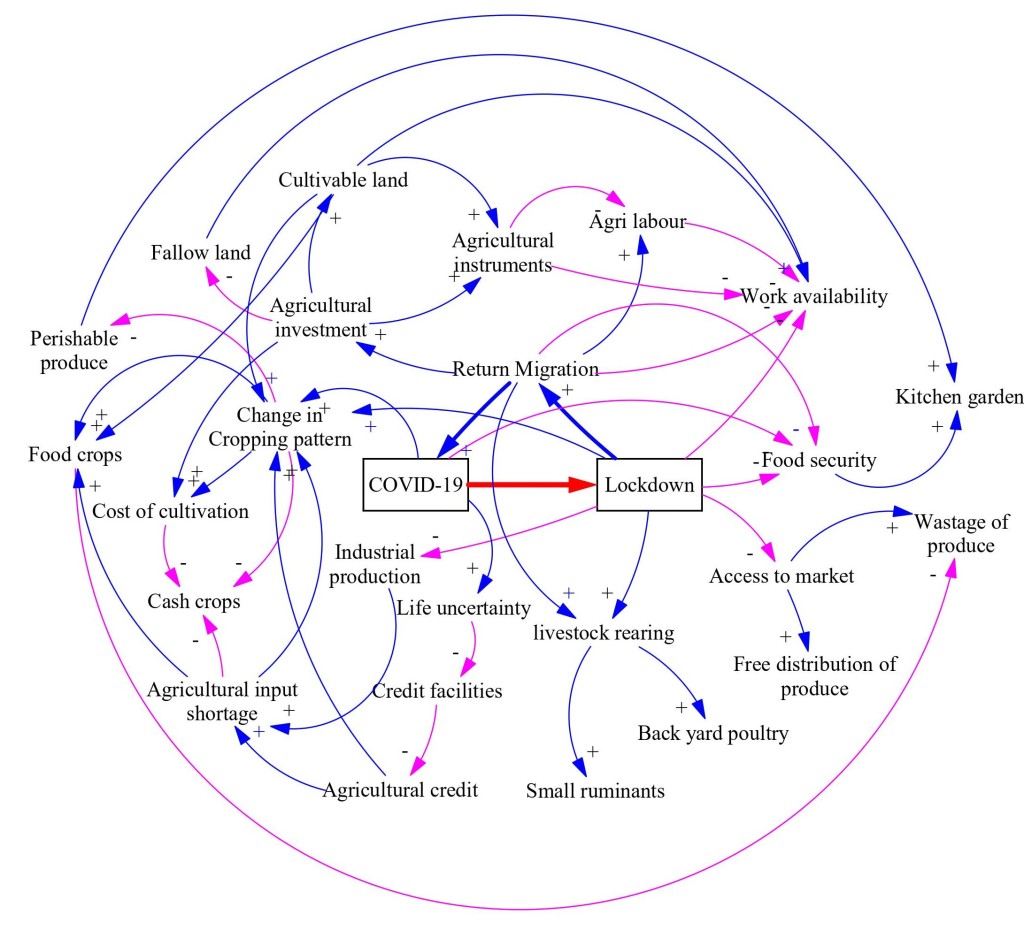

This diagram shows the interlinkages between a majority of the aspects affected by COVID-19 and the lockdown. The blue arrows indicate an increasing effect, while the pink arrows show the decreasing impact of a linked factor at the other end. As we see in the diagram, the worsening situation of COVID-19 compelled the government to impose a lockdown that decreased market access; hence, crop production wastage. The reduced market access increased the free distribution of farm produce in the village, which is a pure loss for the farmers, but it helped many poor households and returning migrants access food in the normally stressful summer months. The lockdown, saw people returning from cities to villages. Many invested in agriculture and related activities which increased the area under cultivation and increased work opportunities in the villages when needed. Unfortunately, not only did the migrants bring agricultural investment to the village, but a few also brought the COVID-19 virus.

Farmers have now learnt to pay attention and plan their crops, not only according to the weather behavior, but also to the waxing and waning of COVID-19 infections. Both these affect agriculture and their income.