~by Omkar Hande and Saurabh Purohit

Photo Credit: Saurabh Purohit

Plastic’s Dominance and the Urgency for Solutions

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that plastic dominated the last century as an omnipresent component of the global economy. It has infiltrated every ecosystem and continent on Earth. Plastic is present in every product we use daily, from writing pens and footwear to aircraft parts and weapons. Wherever you go, plastic is there.

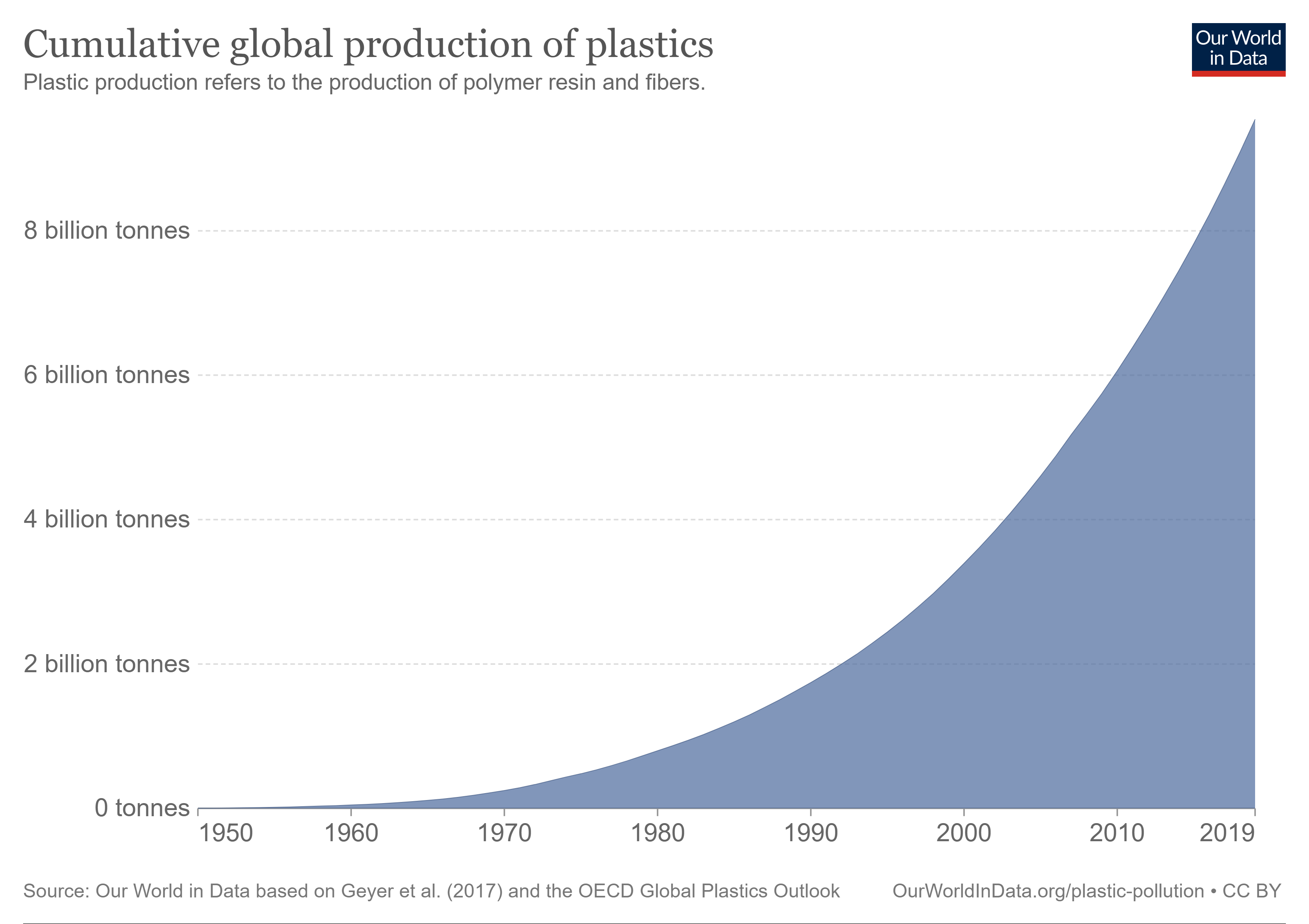

By 2019, the world had already produced a staggering 9.5 billion tonnes of plastic, surpassing the global population of 7.7 billion (Pison 2019). This means that there was more than one tonne of plastic for every person on the planet (Fig 2).

The COVID-19 pandemic has further contributed to the accumulation of plastic waste in our environment. During lockdowns, our reliance on plastic increased significantly due to the widespread use of sanitary items, medicines, and masks. This has added to the already mounting plastic waste crisis.

The current economic model follows a take-make-waste approach, where we extract oil and natural gas to produce plastic, only to dispose of them as environmental waste. This linear process perpetuates the problem and exacerbates the environmental impact of plastic.

Source: OurWorldinData

This year, World Environment Day focused on “Solutions for Plastic Pollution,” and at W-CReS, we saw it as a perfect opportunity to reflect on the evolution of plastic, from its modest origins to its current status as one of the most significant environmental challenges we face on a global scale.

What is Plastic?

Plastic is a versatile material encompassing a wide range of synthetic and naturally existing polymer substances. These substances have the remarkable ability to be shaped into various forms through the application of heat and pressure. The term “polymer” originates from two Greek words: “poly” meaning many, and “meros” meaning parts or units. In essence, plastic is composed of numerous repeating units known as monomers. The process of combining these monomers, such as ethylene gas, through applying heat and pressure is referred to as polymerization.

The Invention of Plastic: Parkesine and Bakelite

Parkesine, the First Artificial Plastic

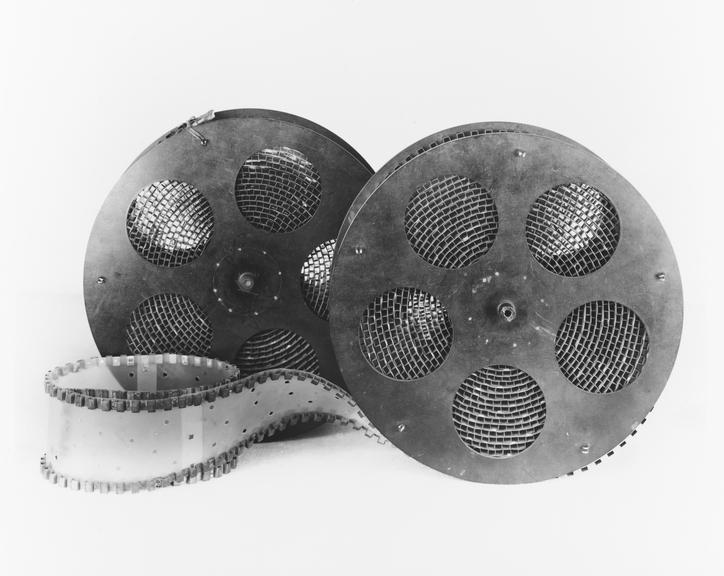

In 1862, Alexander Parkes introduced the world to Parkesine, the very first artificial plastic. This groundbreaking material was created by treating cellulose with nitric acid and a solvent. Parkesine gained immense popularity under the commercial name “celluloid” and laid the foundation for the cinema industry (Fig 3).

Photo Credit: Science Museum Group Collection

Bakelite: The Birth of Fully Synthetic Plastic

Leo Baekeland, a Belgian chemist, revolutionized the world of plastics again with Bakelite’s invention in 1907. Bakelite was the first fully synthetic plastic formed by combining formaldehyde and phenol under heat and pressure. This groundbreaking discovery transformed various industries, from the production of telephones to automobile accessories (Fig 4).

(Source: Pixabay)

Polyethylene: The Game Changer

While Bakelite enjoyed widespread popularity, its rigid nature and limited flexibility hindered its application across various industries. This sparked extensive research and development efforts by individuals, institutions, and companies, all striving to invent a solution that could use the waste materials generated by the oil and natural gas processing industries. It also prompted collaborations between chemical and oil companies, such as the notable partnership of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), which stumbled upon a groundbreaking discovery: Polyethylene.

Polyethylene proved to be a game changer, thanks to its remarkable durability, cost-effectiveness, chemical resistance, and flexibility, earning it a household reputation. This versatile plastic can be further classified into two main types: High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), widely employed for manufacturing shampoo bottles, grocery bags, and more, and Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE), commonly used for producing bread bags, plastic films, and other similar products (Fig 5).

Photo Credit: a) Pixabay b) Saurabh Purohit

Another remarkable breakthrough occurred with the development of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), a plastic that has significantly replaced glass bottles in many applications. PET’s lightweight nature, reduced fragility, flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and reusability have propelled its widespread adoption (Fig 6). It has emerged as a preferred alternative, offering numerous advantages over traditional glass containers.

Photo Credit: Saurabh Purohit

The Associates: Exploring Different Plastics

-

Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC/Vinyl):

PVC, a highly popular thermoplastic, is renowned for its exceptional durability and resistance to weather conditions. It has become a preferred choice over traditional iron/steel pipes due to its outstanding longevity and ability to withstand the elements. Consequently, PVC finds extensive use in the building and construction industry. Additionally, PVC’s non-conductive nature makes it well-suited for applications in cables and wiring (Fig 7).

Photo Credit: Pixabay

-

Polypropylene (PP)

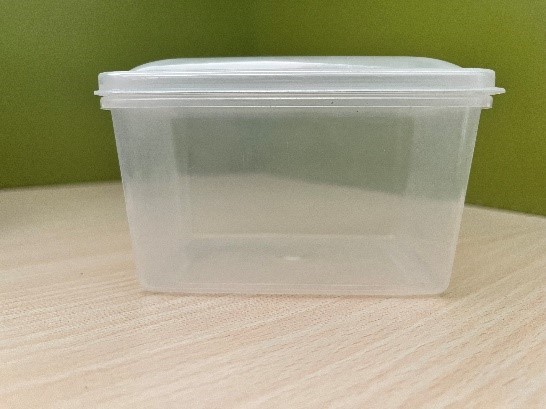

Polypropylene, often referred to as a commodity plastic, is widely utilized in the production of everyday items. While sharing similarities with polyethylene, polypropylene exhibits greater thermal resistance and hardness, making it a preferred material for the food packaging industry. Its durability and reduced brittleness also make it ideal for manufacturing hinges (Fig 8).

Photo Credit: Saurabh Purohit

-

Polystyrene (PS)

Polystyrene serves as a versatile, general-purpose thermoplastic with a wide range of applications. It can take various physical forms, each tailored for specific uses. PS foam is commonly employed as an insulating material in the electronics industry and for manufacturing cups and plates. The solid form of PS finds its place in the medical field, being used to create petri dishes, test tubes, and housing casings. Notably, PS possesses high recyclability and the unique ability to revert to its original state (Fig 9).

Photo Source: www.windsorpack.com

While there are other types of plastics, their contribution to plastic pollution is comparatively lower compared to the categories mentioned above.

Plastic: From Boon to Bane

Plastics possess remarkable properties such as durability and chemical inertness, which make them resistant to decomposition under natural conditions. This inherent quality, coupled with excessive plastic consumption, has resulted in the accumulation of plastic in our environment (MacLeod et al., 2021). The longevity of plastics is so significant that remnants of early-generation plastics can still be found within terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Table 1 provides estimates of the decomposition time for major types of plastics, highlighting their prolonged persistence in the environment.

| Plastic | Decomposition Time | Same Time Since |

| Plastic Grocery bag | 20 years | The US Invaded Iraq (2003) |

| Plastic Beverage Holder | 400 years | First Folio of William Shakespeare Published (1623) |

| Plastic Bottle | 450 years | Completion of Agra Fort by Akbar (1573) |

| Fishing Line | 600 years | Battle of Cravant (1423) |

Table 1: Estimated decomposition time for major types of plastics

(Modified from NOAA.gov)

The extensive use of plastic coupled with limited recycling practices has brought the term “plastic pollution” to the forefront. It refers to the intrusion and proliferation of plastic materials, resulting in adverse ecological and environmental impacts (Iroegbu et al., 2021). The detrimental effects of plastic pollution were initially observed in marine biodiversity during the 1980s (Napper and Thompson, 2020).

Due to its toxic nature, plastic impedes the ability of biodiversity to deliver ecosystem services to their full potential. Unlike noise pollution, plastic pollution can migrate across vast distances, and humans play a significant role in dispersing plastics to the remotest corners of the Earth. Consequently, plastic pollution poses significant threats to various ecosystem components, particularly aquatic systems, and can have detrimental effects on biodiversity.

Components of Plastic Pollution: Macro and Microplastics

Plastics can be categorized into two main groups based on their size: macroplastics (≥5 mm) and microplastics (<5 mm) (Gao et al., 2022). Macroplastics physically impact organisms, with marine environments experiencing pronounced effects, such as entanglement (Fig 10). Ingesting macroplastic items can lead to intestinal and digestive complications.

Photo Credit: Ewan Edwards / The Clipperton Project

Microplastics, on the other hand, can either remain in the soil or directly reach aquatic environments through sewage sludge. Due to their small size, microplastics are ingested by a range of organisms, including protozoans and mammals. Ingesting microplastics can cause damage to the intestinal and soft tissues and disrupt feeding systems in marine organisms. Furthermore, microplastics can enter the food chain, compromising the health of various organisms.

Plastic pollution has the potential to alter ecosystems and hinder their ability to adapt to climate change. It can disrupt natural habitats and have far-reaching social and economic consequences, impacting the well-being of millions of people.

Solutions to Plastic Pollution: Taking Action

Plastic pollution is a global challenge, and while completely eliminating plastic may not be feasible, we can take several proactive measures to control its impact. Here are some key solutions:

- Remember to “Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle”: Adopt a mindful approach to consumption, prioritize the reuse of items, and ensure proper recycling of plastics.

- Avoid Single-Use Plastic: Minimize the use of single-use plastic items such as straws, bottles, and bags, opting for reusable alternatives instead.

- Use Biodegradable Packaging: Choose packaging materials that are biodegradable or compostable, reducing the environmental burden of plastic waste.

- Raise Awareness about Plastic Pollution: Educate others about the harmful effects of plastic pollution and the importance of responsible plastic use.

- Avoid Extras during Takeaways: Opt out of unnecessary plastic cutlery, condiment packets, and other extras when ordering takeaway food.

- Carry Your Bag During Shopping: Bring your reusable bags to reduce reliance on plastic bags.

- Segregation of Waste: Implement proper waste segregation practices, separating plastic waste from other recyclable materials.

- Explore Chemical and Technological Interventions: Support research and development of innovative solutions such as chemical recycling and new materials that offer more sustainable alternatives to traditional plastics.

Indian Initiative for Combating Plastic Pollution

Recognizing the imminent threat of single-use plastic, the Indian government has taken action. The Plastic Waste Management Amendment Rules 2021, effective from 1st July 2022, prohibit the use of certain single-use plastic items. The banned categories include earbuds with plastic sticks, plastic sticks for balloons/flags, plastic flags, candy sticks, ice-cream sticks, polystyrene (thermocol) for decoration, plates, cups, glasses, cutlery, and thin plastic or PVC films used for wrapping sweet boxes, invitation cards, cigarette packets, or banners less than 100 microns thick.

The Way Forward

Addressing the pervasiveness of plastic pollution requires a collective effort and behavioural change within our communities. Organizations like WOTR have played a vital role by raising awareness about the detrimental effects of single-use plastic and promoting eco-friendly lifestyles. By embracing sustainable alternatives and working together, we can make a positive impact on our environment.

Further Readings

- Gao, Haihe et al. 2022. “Macro-and/or Microplastics as an Emerging Threat Effect Crop Growth and Soil Health.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 186: 106549.

- Iroegbu, Austine Ofondu Chinomso et al. 2021. “Plastic Pollution: A Perspective on Matters Arising: Challenges and Opportunities.” ACS Omega 6(30): 19343–55.

- MacLeod, Matthew, Hans Peter H Arp, Mine B Tekman, and Annika Jahnke. 2021. “The Global Threat from Plastic Pollution.” Science 373(6550): 61–65.

- Napper, Imogen Ellen, and Richard C Thompson. 2020. “Plastic Debris in the Marine Environment: History and Future Challenges.” Global Challenges 4(6): 1900081.

- Pison, Gilles. 2019. “Tous les pays du monde.” Population & Sociétés 569(8): 1–8.