By Arpan Golechha

Water is amongst the most important ecosystem service, especially so in the semi-arid regions in India. The village of Tigalkheda lies in the Jalna district of Maharashtra, characterized by recurrent droughts and dry spells. At the edge of the village, 14 farmers have pooled in their water resources to combat these climate stresses and use this water to cultivate over 32 acres (12.8 ha) of land with greater water-use efficiency, rules for water-use, crop planning and a self-regulated institution connected in the agricultural value chain.

Group Micro-Irrigation Model

The Group Micro Irrigation (GMI) model, as it is called, is based on the principle that water is used as a common good rather than a private good which would reduce the overexploitation of water resources. However, the purpose of GMI stretches beyond water conservation and involves water-use efficiency, good agricultural practices, crop planning according to soil type and water availability etc. There were two main purposes of bringing together farmers together- firstly, judicious use of water and secondly, to see if benefits could be generated using economies of scale.

I visited Tigalkheda in November 2018 – the time for the winter crop in the region. I was expecting dry farms with parched crops since most of the farms in the area presented this picture. The year had been the worst drought in the area since 1972 as per the residents there. At the edge of the village, 14 farmers had pooled in their water resources to practice agriculture on 32 acres with cotton, maize and soybean being the major crops in the aforementioned area. The farms were unbelievable to witness, covered in green. The farmers had been practicing a Group Micro Irrigation model with certain Good Agricultural Practices like vermicomposting, organic fertilisers and pesticides, crop spacing, crop rotation etc.

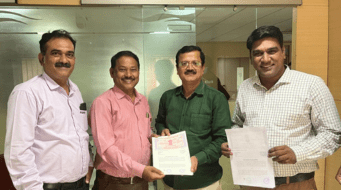

With the help of Watershed Organisation Trust, these farmers were trained in agricultural practices, use of drip irrigation, and cooperation over water Resources. They have now, transformed into a self-help group called Jalsamruddhi Shetkari Bachat Gath (Farmers’ Self-help Group for Prosperity through Water) and maintain a board with a set of rules they follow (at the pump site for drip irrigation). I saw a register where they maintain the minutes of their meetings, the decisions for the crops they take and who takes what crops in which season. This was astounding- a governance model which was not formal but functioned very efficiently.

Socio-economic considerations

The model had underlying biophysical and socio-economic considerations as well. The 32 acres selected for the intervention drew water from the same aquifer and had been historically owned by a single family which had, over the years, divided their land amongst their sons and daughters. This is to highlight the importance of social structures and biophysical factors in the functioning of these models and leading to effective governance at the ground level.

This Group Micro Irrigation (GMI) approach is an example of self-regulation at the lowest of levels where a group of farmers has come together to modify their behavior of competition in water sharing to help avoid overexploitation of the resource and promote sustainability. The “Civic-minded” ideology behind the same is that of sustainability which required that the farmers be “Educated” about the benefits of avoiding “competition” for water and modifying their “behavior” into a more cooperative unit/collective rather than individuals with selfish agenda of claiming a larger share of the available water resources for themselves.

It worked, I feel, because of two reasons; firstly, because the 14 farmers in the group were related, albeit two or three generations ago, and had preserved that bond amongst their households. This enabled them to have a clear leader- the eldest of them. Secondly, this provided them an agency that was absent to them- a social structure to lean on. They were deriving economic, cultural and social benefits from this institution and that helped them even connect to Farmer Producer Organisations (FPO), get better prices for their produce and reduced prices for inputs.

In November 2018, the cotton fields on these farmers’ land were giving an estimated yield of about 50 quintals/ha (20 qtl/acre) where their counterparts were getting just over half that yield. Due to the drought, the cotton prices shot up and the farmers who grew cotton received a windfall, the quantum of which was very high in Tigalkheda’s Jalsamruddhi group. However, the windfall is not the only benefit they derive.

Rotation of crops

The group rotates their crops to maintain soil quality, uses organic inputs and drip irrigation. They have thriving livestock and cropping due to the water saved through low competition and water-use efficiency (drip systems). They could avail government subsidies for their drips, and products like crop insurance were also adopted by most of the farmers. The linkages of the group with the FPO has also increased their market access, their purchasing power and risk-taking ability while the practices have improved the longevity of the ecosystem services they rely on.

This model is being implemented widely by Watershed Organisation Trust in several parts of Maharashtra and Telangana with various irrigation sources- bore-wells, dug-wells, ponds, farm ponds, etc. The model shows promise of succeeding in helping farmers cooperate in using ecosystem services while avoiding the Tragedy of Commons. These ground-level governance measures are a necessary step towards adaptation to Climate Change and extreme events resulting from the former.