By Nikhil Nikam

“Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel prizes – one for peace and one for science.” – John F. Kennedy

When the Indo-German Watershed Development Programme (IGWDP) was initiated in 1989 and operationalized in 1992, the overall goal of the programme was poverty reduction through people-managed environmental regeneration and resource mobilization along watershed lines. Bhojdari, in Ahmednagar district, was one of the project villages. Initially, from the year 1995 to 2002 various drainage line treatments and area treatments were initiated in this village. Meanwhile, several committees were formed to delegate the authority of work and to maintain the watershed structures even after the project is over. A watershed committee was formed to look after the watershed structures, forest management committee to make sure the regulations related to the forest are being obligated, and a biodiversity committee to register and to keep an eye on the local biodiversity. Also amongst them were social committees like self-help groups, youth groups, farmers’ groups, and Samyukta Mahila Samitis that were formed.

Over a period of time, the watershed treatments started showing positive impacts on the availability of ground and surface water reservoirs. It did not take much time for farmers to drop the indigenous food crop cultivation practices and shift to today’s demand-driven cash crop market. And due to the availability of water, there was a drastic increase in the number of wells and borewells, that ultimately encouraged greater exploitation of groundwater. As time passed, indigenous crops like Pearl Millet, Sorghum, and Groundnut were substituted by water-intensive crops like Soybean, Pomegranate, Sweet lime, Green peas, Tomato and Onion. Even the grasslands and pasture lands were brought under cultivation. Due to the increased cultivable area and availability of water, in a short span, the farmers started to make a considerable amount of profit and on the other hand, farm laborers, landless farmers, and non-farm laborers were happy to get employment in the village itself.

The year 2016 saw severe drought. The kharif season passed pretty well using alternate irrigation sources. But in rabi and summer season farmers faced water scarcity. Farmers who owned dug wells were the most affected. The ones who owned borewells were comparatively affected less. Therefore, this led the farmers to dig more borewells, especially in the summer season. But due to lower rainfall and over exploitation of groundwater from borewells too, this didn’t help for long. Only a few farmers who had numerous sources of irrigation managed to sustain their crops. Most of the horticultural farmers were compelled to chop off their crops.

In the second drought year (2017), by giving up on the water-intensive crops farmers went back to cultivating their indigenous crops, which were pearl millet and soybean. During this year drinking water was another major issue. In the months of late winter and summer, a common dug well which supplies water to the entire village was not able to supply enough drinking water. So the additional need was fulfilled by getting water tankers from outside.

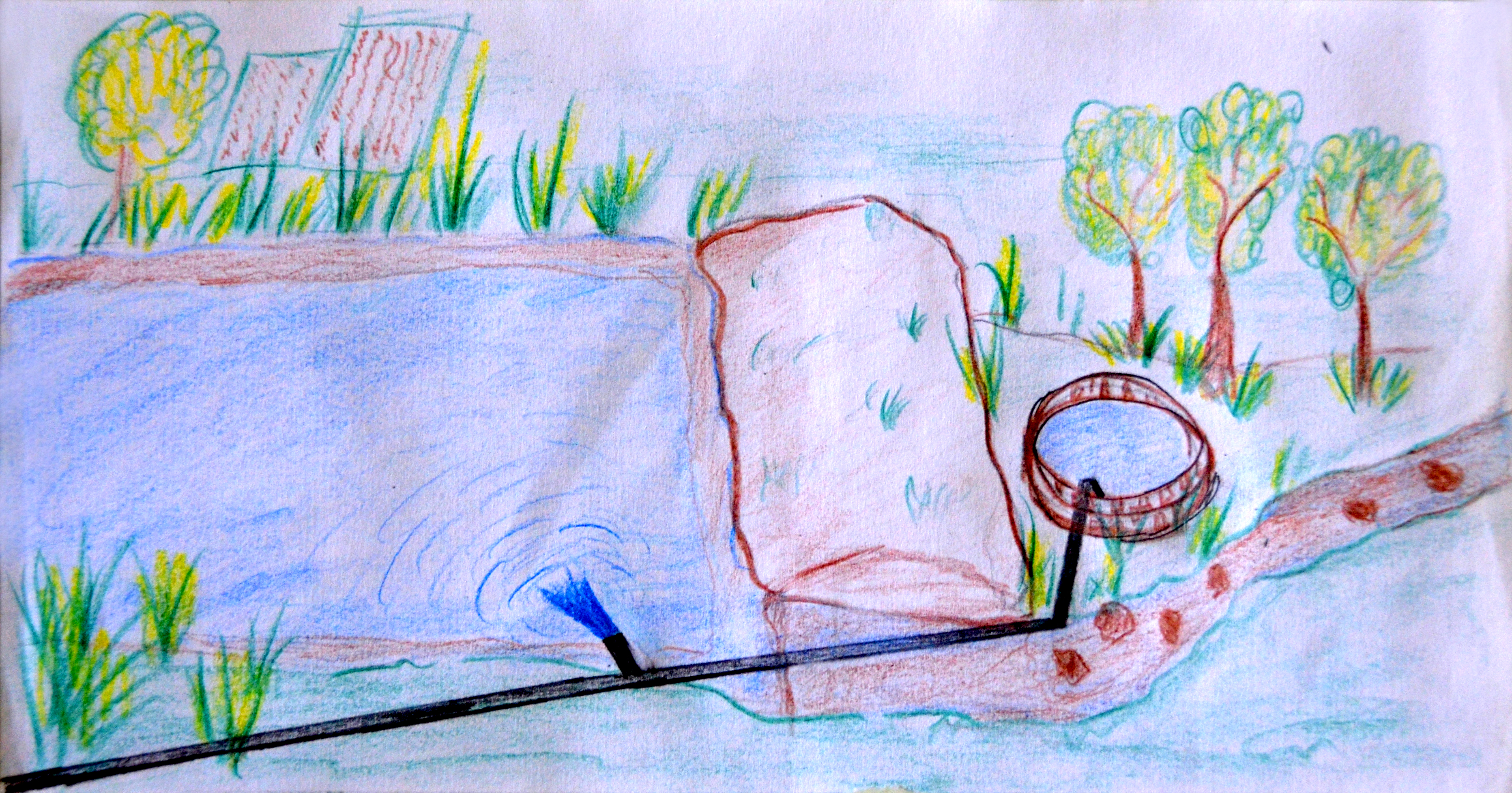

The year 2018 saw average rainfall. But due to erratic and extreme rainfall events, the watershed structures were quickly filled up and streams started to flow. A common dug well of the village was constructed in one of these streams. Water from this well, with the help of an electric pump, was then lifted to the village’s common water tank. This water tank has been a source of tap water to individual households.

After the discussion between the committees, they came up with an idea of not letting water from the dug well to be discharged in the stream and it could only be possible when well water has to be discharged in some other direction. So they made one more outlet in the pipeline, which would drain water in the earthen nala bund. Every day, they pumped water from dug well to a drinking water distribution tank. Once the distribution tank is full and still water is there in the well then that water is drained back into the earthen nala bund. Draining the well is important to stop the discharge of water into the stream. And it worked! This way, the discharge from well into the stream stopped completely.

Villagers said that, in 2019, despite being a drought year, they had sufficient drinking water till the beginning of April. Whereas, Last year in the same case scenario, villagers had to call-in the water tankers from the middle of January. Through this initiative, the water became available to satisfy the thirst of the villagers and the domestic animals during the harsh summer and also delayed the procurement of water tankers at least by two-and-a-half months. One can say this brings out the truth in the proverb that that “The one who suffers the most could come up with the best possible solution.”